Mons is one of those battles that evokes great pride amongst many people in Britain today. The mere mention of Mons conjures up images of British soldiers digging their heels in, against a German army who outnumbered them significantly. The Germans who had enjoyed a deal of good fortune in the opening month of the war marched through Belgium like a school bully intent on inflicting pain and misery to his next victim. But they would be unprepared for the blast of fire that would be dished out to them by the stubborn British. For two days the British held their nerve, before they reluctantly withdrew in the face of the unabated pressure, heaped on them by the Germans. What followed became known as the great retreat, a race to outrun the Germans, to redraw to a new defensive line in the sand. Mons would be superseded by larger and far more important battles in the months and years that followed, however the defense at Mons would be forever supplanted into the British subconscious.

With great reluctance the British government viewed the violation of Belgian’s neutrality, as enough reason, to enter the Great War on the side of her allies, France and Belgium, on August the 2nd 1914. With Britain’s declaration of war came an inundation of support and volunteers. Many young men felt instantly compelled to enlist, however it wasn’t going to be difficult to arouse support. In all, 150,000 men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were ready for mobilization within the week. On the 9th August, advanced parties of the BEF had already secretly landed in France. They would be charged with the duty of protecting the French left flank with the main British force joining their brothers-in-arms soon after.

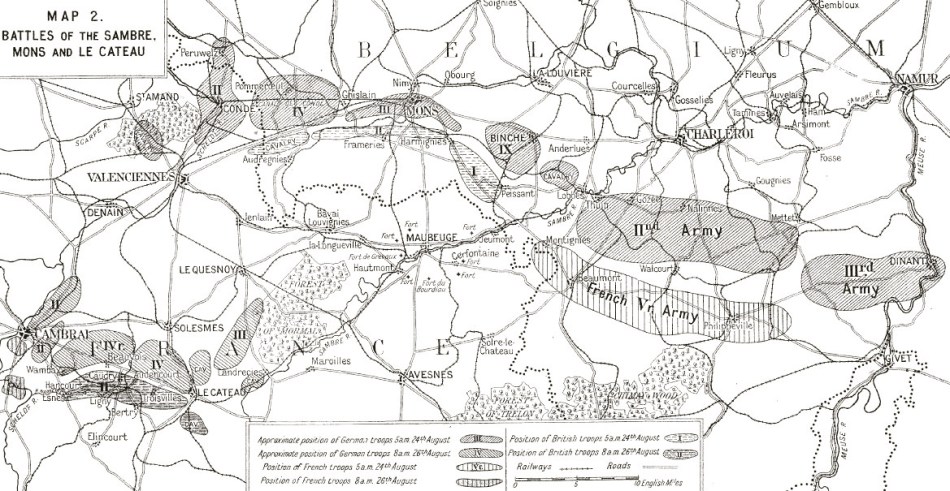

By the 20th August the main column of the BEF started their march to positions on the left of the French General Lanrezac’s Fifth Army, at Maubeuge on the River Sambre. They were then asked to continue their march across the border of Belgium where they would take up position around Mons. It was during this period of movement that neither the British nor the Germans First Army, under the elderly General von Kluck, knew of each others direct presence until advance patrols managed to bump into each other near Obourg. It was here, in the village Obourg, a few miles away from the town centre of Mons that the British fired their first shots in anger. It also became the site of where the first British soldier, by the name of Private John Parr, was killed in action.

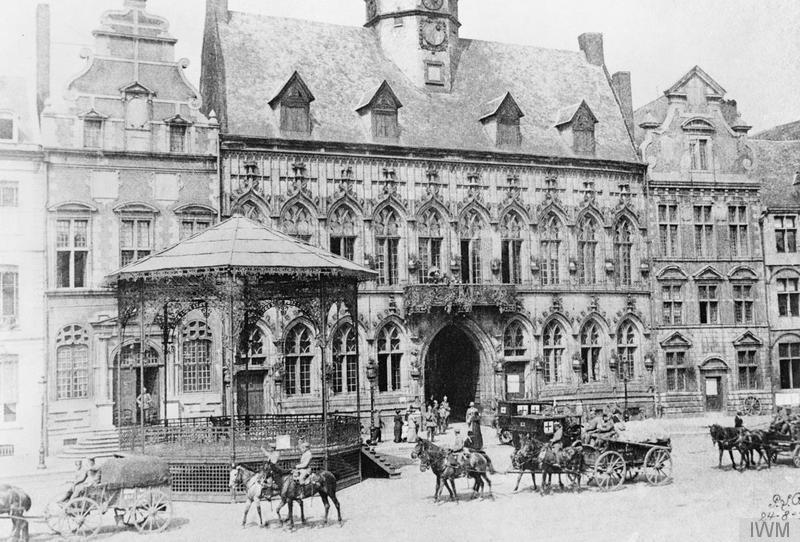

Soldiers of ‘A’ Company 4th Royal Fusilier rest in the Grand Place at Mons. Soon these men would be facing the Germans in positions on the Canal de Conde at Nimy.

On that same day that Private John Parr was killed, the British had planted themselves into the heart of Mons. Hot, thirsty and tired the British rested while waiting for further instruction from their commanders. What they eventually learned was that the French Fifth Army, led by Lanrezac had suffered defeat on the Sambre, and at the request of Lanrezac, the BEF commander General John French, agreed to hold the line on the Mon-Conde Canal for a whole day. Its aim was obvious, to prevent the advancing German First Army from threatening the French left flank any further.

Early on the morning of Sunday 23rd August, a British defensive line stretched along the Mons-Conde Canal in anticipation of a German onslaught. Here, the British entrenched themselves, particularly in the mining district of the town, where buildings and country houses provided good defensive positions. The mining spoil heaps were also used to provide great observation posts. However, if we could direct any criticism at the British defences, it would have been in regards to their failure to wire all the bridges over the canal. Nonetheless, this small highly trained and professional British army, that stood awaiting the Germans was eager, ready and equal to the task of trying to defend Mons. This would be Britain’s first military engagement on continental Europe, not since the Battle of Waterloo. It would also be the first British battle, not only in a built-up, industrial town, but also in an environment caught up amongst a local population.

In the battle of Mons (proper) on the 23rd August, the British witnessed the tentative movements of Germans approaching them. Almost suddenly, a sizable grey mass of German soldiers followed breaking out into view. As the first wave of Kluck’s army pushed towards the Conde-Canal the British opened up with a barrage of ‘rapid fire’. Trained to deliver fifteen rounds a minute, hundreds of Germans at a time, collapsed along the stretch of the Conde-Canal. Corporal Holbrook of the 4th Battalion Royal Fusiliers probably best sums up what happened, “You’d see a lot of them coming in a mass on the other side of the canal and you just let them have it. They kept retreating, and then coming forward, and then retreating again.”

Throughout this series of ‘en masse’ rushes, the Germans were able to gain a foothold along the Canal, however, at great cost. Still though the stubborn British resistance had worked to stall the Germans at Mons. By the evening, as historian John Keegan points out, “…the Germans of von Kluck’s army slept where they tumbled down, exhausted…with the day’s work of carrying crossings over it (the Conde-Canal) to do it all over again on the morrow.”

The British, by the evening were also exhausted, somewhat in awe and in shock of having to repel attack after attack by the Germans, who seemed to disregard the casualties that kept on rising steadily throughout that first day. With Mons on fire, and many of the other surrounding towns too, the British reluctantly fell back and withdrew to a new defensive position during the evening of the 23rd.

The scenes that unfolded on that first day would enter into British military folklore. Historian Peter Hart states that “The myth (of Mons) is one of a heroic successful defence, with well-trained British ‘Tommies’ mowing down hordes of Germans repeatedly attacking in mass formations.” But Hart goes onto explain that this heroic view of the battle, like the ‘Angels of Mons’ myth just simply didn’t happen. The reality of the day was that the Germans simply ‘retired’ for the day. Their casualties had exceeded numbers far more than they would have liked and to add to their concerns they feared a possible British counter attack. In General von Kluck’s memoirs of the campaign, he wrote that he wasn’t happy at all that his army had suffered large casualties against what he thought was a small British force. (German casualties are still a little unclear, but they are estimated at around 5,000 for the battle of Mons, while the British lost over 1,600 soldiers.) Apparently at the end of the first days fighting, and after being informed of their great losses, he changed his mind believing that the small British force was, in fact, a force upwards of six divisions. He would later be horribly applaud to found out that the Germans, in actual fact, outnumbered the British 3 to 1. (That was roughly six divisions to four.)

The feared counter attack of the British never came, instead the BEF were forced to fight another day (24th) of defensive action. Throughout this second day of action, the Britain continued their withdrawal, to prevent the Germans from encircling them. Here, the great retreat had truly begun in earnest, with the Germans in hot pursuit. At dawn on the 26th, the British came under extraordinary pressure from the chasing Germans, this time at Le Cateau. The BEF were forced to fight various holding actions, losing around 7,800 more men killed, wounded and or taken prisoner. The action at Le Cateau eventually succeeded in throwing the Germans back. A buffer of two days march were gained and the British surprisingly remained unmolested for almost the next ten days as they marched all day long, mile after mile, sleep deprived and with very little food, all the way to the River Marne.

German soldiers of the 18th Division, IXth Corps, in the Grand Place, Mons after the capture of the city.

Historians will argue about the significance of Mons and Le Cateau until they go blue in the face. Yes, the Germans broke through and took the town of Mons. However, the brave actions of the British stalled the Germans long enough for the British to join their French allies. Exhausted and in a very bad state, the British would regroup alongside the French army, but whether or not they would be able to stand and fight again, only time would tell.

Photo Credit: The header image is entitled the ‘Wounded heroes of the Battle of Mons’. It is part of the George Grantham Bain Collection and courtesy of the Library of Congress without any known copyright restrictions. The illustration of the British holding a position on the Mons-Conde Canal is by flickr user Jane Jones. I make use of this image under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 license. The image of German troops of the 18th Division, IXth Corps, in the Grand Place, Mons after the capture of the city is courtesy of IWM and used under their terms and conditions of fair dealing. All other images are in the public domain.

Notes and Further Reading

“You’d see a lot of them coming in a mass…”, Britain at War Magazine, First World War: An illustrated History, 2014, p.15.

B.H. Liddell Hart, A History of the First World War, Pan Books, 2014.

“The myth (of Mons) is one of a heroic successful defence..”, Peter Hart, The Great War 1914-1918, Profile Books, 2013, p.54.

Max Hastings, Catastrophe, William Collins, 2013.

“…the Germans of von Kluck’s army slept…”’ John Keegan, The First World War, Hutchinson, 1998, p.99.

Pingback: The Angels of Mons | If It Happened Yesterday, It's History

Yet another great addition to this series, Robert! Amazing read.

Pingback: A history of the First World War in one hundred blogs ! No.5 Mobilisation and the groundswell of enthusiasm ! | If It Happened Yesterday, It's History

Pingback: The Grand Place, Mons, Belgium. (Past and Present) | If It Happened Yesterday, It's History